"You think the Beatles are exciting? These fellas run over the Beatles.

Here they are: Hub Kapp and the Wheels!" -Steve Allen, 1964.

by Dan Nowicki

Listen up, Americans! Hub Kapp and the Wheels invented punk rock. And maybe even glam and heavy metal for that matter. Sure, sure. How many times have you heard that old saw? But this one makes sense. Sorta.

Hub Kapp and the Wheels was the notorious joke rock and roll band that was born on a hip Phoenix, Arizona, kids’ television show, took Hollywood by storm at the height of Beatlemania and has continued to confound music scholars and record collectors to this day.

For all its phoniness, the group was a huge attraction in Arizona, scored regional hits and was a major influence on the embryonic Phoenix ’60s rock scene. Among Hub Kapp’s fans was the young Vincent Furnier, who with his Cortez High School buddies would form their own Beatle parody band called the Earwigs. That band, of course, would become the Spiders and then the Nazz and eventually Alice Cooper.

The Coop has never hidden his affection for The Wallace and Ladmo Show, the groundbreaking kiddie program that aired on KPHO-TV (Channel 5) under various titles such as It’s Wallace? and Wallace and Co. for an amazing 35 years between 1954 and 1989.

It was on It’s Wallace? that Hub Kapp and the Wheels first rose to prominence in 1963. "If you didn’t grow up here, you may wonder why people still talk about it years after being off the air," Cooper himself explained in an hour-long 1999 documentary on the Wallace show that he narrated for KPHO. "The reason was simple: it was different. The humor was rebellious, demented, out-of-whack. Imagine the effect it had on kids who watched. But enough about me…"

The show featured Bill "Wallace" Thompson as straightman to rubbery physical comic Ladimir "Ladmo" Kwiatkowski. The duo was joined by Pat McMahon, the so-called "McMahon of a thousand faces" who portrayed a variety of oddball characters such as Gerald Springer, the mean-spirited spoiled brat; Captain Super, the archconservative comic-book hero; Marshall Good, the out-of-work cowboy actor, and Aunt Maud, an abrasive old lady who would read twisted and macabre stories to the kids. Guitar prodigy Mike Condello was the musical director.

McMahon, with an outrageous pompadour wig, long eyelashes and fake eyebrows and sideburns, also was the legendary Hub Kapp, the godfather of punk who taught Alice Cooper a thing or two about shock rock theatrics in falseface.

"Alice continues to insist that he was inspired by a combination of Hub Kapp and Aunt Maud," quipped McMahon, now an on-air personality with Phoenix news radio giant KTAR. "We certainly didn’t consider ourselves pioneers or visionaries. We considered ourselves guys who were doing a comedy show back home that was the Monty Python for kids. Hub Kapp was just one of a whole bunch of characters that we did."

According to the TV script, Tony Evans, a popular disc jockey known as "the Fearless Leader" at Phoenix Top 40 station KRIZ, discovered the grotesque Hub Kapp working at a gas station in Cotton Corners, Tennessee. Since Hub Kapp was Phoenix’s answer to Elvis, the Wallace and Ladmo gang recruited Evans to fill the Col. Parker role. In fact, Evans would later prove pivotal in helping a number of bona fide local rock acts such as Floyd and Jerry, the Pendletons and the Bittersweets and is credited with breaking Dyke and the Blazers’ home-cooked "Funky Broadway" in 1966.

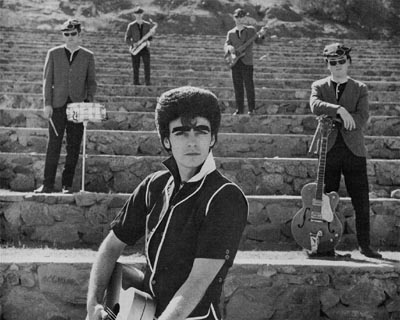

"Supposedly Tony Evans was driving through Tennessee and had to have some automobile work done and discovered Hub and the Wheels in the grease pit," McMahon said. But Hub Kapp and the Wheels were true proto-punks. Wallace originally had dubbed them Hub Kapp and the Tire Slashers, but KPHO management quickly put the kibosh on that. The Wheels wore dark sunglasses, black berets and sullen expressions and adopted the punky pseudonyms Rip Kord (Condello), Ry Krysp (bassist Bob Dearborn) and Ty Klyp (drummer Rich Post). Occasionally they were joined on stage by fourth Wheel Terry Kloth (keyboardist Ted Harpchak).

You want D.I.Y. attitude? Hub Kapp and the Wheels merely declared themselves instant Rock and Roll superstars, and it was so. Buoyed by the local television exposure, they immediately began drawing huge audiences at personal appearances at area high schools and Legend City, Phoenix’s late, lamented Wild West amusement park.

Their 1964 debut single, "Work, Work" on Condello’s Take Five label, was a No. 1 Phoenix smash and shoved the Beatles off the top of the local charts for the first time since they’d come around. The song, an ode to slacking off (to Hub Kapp, work was "a dirty word, the dirtiest word I ever heard") that features some blazing, this-ain’t-no-joke rockabilly fretwork by Condello.

Although an obvious parody group, the musical integrity of the Condello combo still holds up and none of the Hub Kapp records reflect the sneering contempt of, say, a noted rock hater like Stan Freberg.

"We didn’t go out and make fun of the genre," McMahon said. "There was a subtlety to the things that we wrote. I wrote ‘Work, Work’ in about four minutes before the show one day. We thought, ‘What would Hub do?’ Hub would probably think about how to get out of working very hard. So I dashed off the lyrics, we did a blues sequence, and that was it. It was a huge local hit."

The first single’s other side, a call-to-action titled "Let’s Really Hear It (For Hub Kapp)," has its charm as well, although McMahon now dismisses it as "a whole bunch of nonsense lyrics that Wallace made up just so that we would have a B-side." Some sample lines: "Send up flares/ Can’t stand squares/ Mirror, mirror, on the wall/ Who’s the fairest one of all?/ Let’s really hear it for Hub Kapp." Like "Work, Work," the song also has crowd cheering to give it "in-person" appeal.

If the Hub Kapp story ended there, it would have been improbable enough. Instead, that’s when things started to get really surreal. The regional success of "Work, Work" was substantial enough to attract the notice of show-biz industry mullahs in Los Angeles and eventually led to a contract with Capitol Records, home of the Beatles and the Beach Boys, the band’s heroes. Hub Kapp’s alien stage presence proved a perverse attraction to the Hollywood starmakers and it wasn’t long before he and the Wheels were holding court at the Whisky a Go Go on the Sunset Strip and making national TV appearances on the Steve Allen and Joey Bishop programs. All the while, they continued to fulfill their obligations to the Wallace and Ladmo show in Phoenix.

"It was all beyond anything that anybody could ever plan," McMahon recalled. "It was one of those crazy, I-don’t-really-believe-that-this-kind-of-thing-could-happen where in some B-Grade, low budget movie a guy puts a wig on and becomes a Rock and Roll star. We were commuting back and forth doing shows and screen tests for bad beach movies. We did an audition for Shindig and never did hear what happened."

The strangest twist of all was that much of the group’s intrinsic humor was mostly lost on the West Coast. McMahon was bound by contract to never appear sans wig and eyebrows or in any way tip off the Southern Californian public that it was all a gag.

"If you could have been over in Los Angeles with us, you wouldn’t have believed it," McMahon said. "Because it was Arizona who really ‘got it,’ and went along with the joke. It was L.A.sophisticated Hollywood and the big-time show biz peoplewho took it very, very seriously."

McMahon, Condello and company were introduced to the L.A. entertainment media at a major press conference and party at the Capitol Tower. The Wheels were instructed not to utter a word and Hub was told to do all the talking.

"And, of course, I had to wear the entire outfit," McMahon said. "I thought, ‘My God, they are right up in my face. Can’t they tell that this is make-up?’ The mood of it was, if they did think that they were phony eyebrows, nobody wanted to bring them to my attention. They thought I was a burn victim or something."

A recording session at the Capitol Tower produced a sophomore 45, but the results were somewhat disappointing both to the band and record buyers. This time, both sides were covers: Larry Williams’ R’n’B standard "Bony Maronie" and the Everly Brothers’ "Sigh, Cry, Almost Die." The versions were credible if not particularly memorable to anybody other than diehard Hub Kapp fans. Both songs were a bit overproduced and played a little too straight.

"They were OK records, but they didn’t sound like Hub Kapp," Condello would note years later in an interview for a locally published book about the Wallace and Ladmo show. "They didn’t have the content in them that might have given some clue to the personality of the group."

McMahon and the Wheels were conflicted about the way the act was progressing. They were homesick for Phoenix and were beginning to feel guilty about constantly leaving Wallace and Ladmo in the lurch while they pretended to be rock stars in L.A. Eventually, they told the Hollywood agents and record company executives to stuff it.

"Over there I had a bunch of people talking about how they were going to make me the next biggest Rock and Roll star. I kept wanting to lift up the wig and say, ‘Guys, see underneath. Disc jockey and actor,’" McMahon said. "It was clear, for crying out loud. How long could we possibly continue doing this charade? Everybody wanted us to stay. They said you really have something unique. We said, ‘Yeah. We have jobs.’"

Back in Arizona, Hub Kapp and the Wheels recorded and released a third and final single on their own Framagratz imprint. It paired the anti-hot-rod anthem "Little Volks" with a cover of the Beatles’ "What You’re Doing" (incorrectly titled on the label as "What You’re Doin’ To Me").

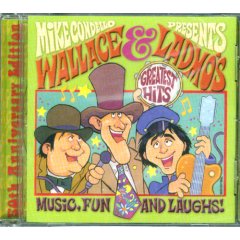

Condello reflected on the Framagratz 45 in the liner notes for a 1994 compact disc compilation of records associated with the Wallace and Ladmo show. "Here was our brilliant two-part plan: A. Somehow get our hands on a Beatle song not yet released in this country. B. Have an automatic smash record in the U.S.A., beating the Fab Four at their own game. Here’s the results: A. We did. B. We didn’t."

McMahon has a different recollection of the events surrounding the single. "I don’t remember sitting there saying that we were going to have a hit," McMahon said. "Condello and I were both Beatlemaniacs. Condello and I went over to Dodger Stadium, in fact, to see them in concert. We picked ‘What You’re Doin’ To Me’ as a piece of material that sort of got lost. It was an album track that nobody paid any attention to. We both loved the song. It was more of a tribute than anything."

In fact, according to McMahon, it was the anti-hod-rod anthem ‘Little Volks’ that got most of the attention upon its release. The song was penned by McMahon and Condello and is one of Hub Kapp and the Wheels’ finest moments. Condello provided the piercing lead guitar, while honorary Wheel Jim Vanier guested on rhythm. (Vanier was in a popular Arizona group called the Vibratos, who had in fact had scored a solid local hit with their cover of the Beatles’ "I’ll Be Back." Their success with a Beatles LP cut might lend some credence to Condello’s strategy.)

Here’s McMahon on the song’s origin: "All you heard were car songs in those days. If you didn’t hear British rock and roll, you heard car songs’Little GTO,’ ‘Little Deuce Coupe,’ and so on. I passed by the parking lot of Washington High School one day, and I remember thinking, ‘Nobody has hot rods. These kids are driving Volkswagens.’ There were a whole bunch of little bugs. I thought, ‘Now, who would write a car song proudly about his Volkswagen?’ It would be a geeky guy. But he wouldn’t think he was geeky. He would be really proud of his machine, and he would be sensitive about it. ‘Don’t make jokes about my little Volks.’ The whole idea was about how he’s out there proudly chugging along in his little 4-cylinder Beetle bug."

If the three singles provide an incomplete picture of Hub Kapp and the Wheels, posterity got a big break recently via the discovery of an amazing unreleased acetate. Had it been pressed up at the time, their names would today be whispered with the same awe as any of the garage-punk bands found on the best Back From The Grave or Teenage Shutdown albums. One side features a guttural, surfed-up take on "Sixteen Tons" while the other is a great raw rocker titled "Don’t Put Me On." The latter boasts some of the most timeless punk prose of all time: "You tell more stories than a fairy-tale elf/ You ain’t fooling anyone but yourself/ Don’t put me on!" Both highlight scorching Condello guitar work.

The "Sixteen Tons" acetate, formally released in 2000 in Phoenix on an already hard-to-find Hub Kapp CD collection, mystifies McMahon. "I don’t ever remember the idea of doing ‘Sixteen Tons,’" he said. "I remember writing the song ‘Don’t Put Me On,’ but I don’t remember recording it. I kind of vaguely remembered the way ‘Don’t Put Me On’ went."

Sometime in 1965, McMahon, Condello and the rest of Wheels decided that Hub Kapp’s race had been run and retired the wig and eyebrows. Around the same time, McMahon was temporarily fired by KPHO and was off the Wallace show for about a year. He worked as a KRIZ boss jock in the meantime, and eventually became the station’s program director. Condello continued making Wallace and Ladmo show music without McMahon. His Ladmo Trio put out the classic Blubber Soul EP, a four-track disc featuring Beatles and Yardbirds songs rewritten about the show’s wacky characters. Later, he formed Commodore Condello’s Salt River Navy Band, which recorded two 7-inch EPs, including the spot-on satire of Sgt. Pepper. The second Commodore Condello EP featured similar goof-takes on Jimi Hendrix and the Bee Gees plus the original "Soggy Cereal," which showed up on an early Pebbles volume years later. Condello must have had the last laugh to see the song offered as an example of semi-serious psychedelia.

When not performing before the KPHO cameras, Condello for years was one of the most respected musicians on the Phoenix scene. His Phase 1 album on Scepter is well-regarded in psychedelic circles and his band Last Friday’s Fire had three singles on Lee Hazlewood’s LHI label. If Condello’s top-notch unreleased Freberg-meets-the-Mothers comedy LPshowcasing great lost classics such as "A Pimple Is A Sometime Thing" and "Public School Lunch"ever officially sees the light of day, his spot in the pantheon of the ’60s pop gods will be secured.

Condello left the Wallace show in the early 1970s and relocated to California. Tragically, he committed suicide in 1995, a victim of severe depression.

"You always hear the interview with the next-door neighbor who says, ‘He was the last guy in the world I ever expected to do this,’" McMahon said. "As close as I was to Mike over the years, I never knew about the clinical depression, and most people didn’t. It must have been insidious. I still miss him."

Still, Hub Kapp and the Wheels’ impact on Phoenix and the Valley of the Sun was so profound that the shockwaves from the band’s impact continue to be felt. Their influence was crystal clear on Valley New Wave bands such as Billy Clone & the Same and the Jetzons, whose 1982 Made in Japan EP was produced by Condello. The entire Hub Kapp saga became the subject of a locally produced stage play that was one of the most popular theatrical events of the past year.

The real Hub Kapp and the Wheels reunited for a 1989 swan song performance at Phoenix’s Encanto Park before tens of thousands of adoring fans. The show was in conjunction with Wallace and Ladmo’s 35th anniversary.

"We made Hub an industrial giant who no longer had to do music," McMahon said. "The Wheels were all working for him and have generous stock-option programs. There’s Hub sitting there with the eyebrows talking about all of the investments that he made. It was a very funny bit."

Amazingly, McMahon said he still gets plenty of offers for Hub Kapp reunion shows, as ridiculous as that would be without Condello. McMahon said he just doesn’t dig the idea of "grandfathers" singing Rock and Roll.

"Even the high school kids are dead now," he said. "That was a long time ago."

*

HUB KAPP AND THE WHEELS DISCOGRAPHY

"Work, Work" (McMahon) / "Let’s Really Hear It (For Hub Kapp)" (Thompson/ Condello/ Dearborn) Take Five 631, 1964. Recorded at Alectron Recording Co., 1344 E. Indian School Road, Phoenix, Arizona.

"Sigh, Cry, Almost Die" (D. Everly/ P. Everly) / "Bony Maronie" (Williams) Capitol 5215, 1964. Recorded at the Capitol Tower, Hollywood. Features long-time L.A. session player Carol Kaye on bass. Produced by Dave Axelrod.

"Little Volks" (McMahon/ Condello) / "What You’re Doin’ To Me" (Lennon/ McCartney) Framagratz F-101, 1965. Recorded at Audio Recorders of Arizona, 3830 N. Seventh Street, Phoenix, Arizona.

"Sixteen Tons" (Travis) / "Don’t Put Me On" (McMahon) Unreleased acetate.

Mike Condello Presents Wallace & Ladmo’s Greatest Hits, Epiphany W&L 1954, 1994. CD-only compilation includes all six officially released Hub Kapp single sides plus essential related 1964-1968 sides by the Ladmo Trio and Commodore Condello’s Salt River Navy Band. Regrettably, it’s out of print but shows up occasionally on eBay.

The Hub Kapp Kollektion, Epiphany 1020X, 2000. Very limited CD only anthology includes all three officially released Hub Kapp 45s plus the previously unreleased "Sixteen Tons," "Don’t Put Me On" and a boss 1964 radio spot by local Phoenix disc jockey Tony Evans for a Hub Kapp and the Wheels gig at his Fearless Leader Club at Seventh Street and Bethany Home Road. This collection was pressed to sell at a local Phoenix play about Hub Kapp’s rise to fame and was never commercially released. Good luck finding a copy.

Compiled by Dan Nowicki for Scram.

Photos courtesy Johnny Franklin.

Wanna read more and see the crazy vintage Hub Kapp pix? Pick up Scram #14